2016–17 Departmental Results Report

(Click to read the Financial Statements, Supplementary Information Tables and Annex.)

ISSN 2561-2158

Table of Contents

Commissioner’s Message

Commissioner

The past year has been one of continuing progress in building trust and confidence in the federal whistleblowing system by providing timely, professional and responsive support to whistleblowers and victims of reprisal. This includes: implementing the first phase of a “LEAN” project to identify operational efficiencies; development of policies that guide our work and provide information to people about what to expect when they come to our Office; and, the publication of our first research paper on the important subject of the fear of reprisal.

Key among the past year’s activities was undoubtedly the parliamentary review of our legislation, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act. This review was long-awaited and overdue. The House of Commons Committee Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates was mandated to carry out the review, and it completed a thorough and extensive analysis of the Act, hearing from a variety of witnesses from across the country and across the world. My Office appeared before the Committee on 3 occasions, and we tabled 16 recommendations for legislative change. These recommendations are specific, substantive and progressive.

Key among our recommendations is the establishment of a reverse onus of proof for reprisal complainants. This would require, once my Office refers a case to the Public Servants Disclosure Tribunal, that the employer prove that reprisal did not occur, rather than requiring the complainant to prove that it did. This recommendation recognizes that an individual complainant has far fewer resources and less power than a government institution. It is an essential step in levelling the playing field for victims of reprisal. Another key recommendation is providing my Office with the ability to obtain evidence from outside the public sector during the course of an investigation, something that we are currently barred from doing under the Act.

These are but two examples of the meaningful progress that my Office is committed to making. I am proud of our recommendations, and I am hopeful that Parliament will adopt them as we move forward in the evolution of our important work. I encourage everyone to consult the full set of 16 recommendations that we made and the final report of the Committee.

I look forward to continuing to work to ensure that we have a whistleblowing system in Canada that reflects our shared values and that builds confidence in our federal public institutions and in the public servants who provide essential services to all Canadians.

Joe Friday

Results at a Glance

Results Highlights

- Tabled sixteen substantive proposals for legislative change to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act to provide a greater level of protection and support for those who disclose.

- Received 81 disclosures of wrongdoing and 31 complaints of reprisal in 2016-17. We launched a record 36 investigations, doubling the number of investigations compared to the year before, while meeting our service standards. Tabled two case reports in Parliament that dealt with serious matters of wrongdoing, both regarding harassment within the public service.

- Commissioned and published our first research paper, “The Sound of Silence: Whistleblowing and the Fear of Reprisal”, which represents an important contribution to the evolution in thinking around whistleblowing.

It is the public interest to maintain and enhance public confidence in the integrity of public servants. In order to achieve this, the Office continued to maintain an effective and timely response to people who approach or interact with the Office. We reached across the public sector to increase awareness and provide clarity about the Act and the role of the Office.

In achieving these results for 2016–17, the Office spent a total of $4.3 million and employed 26 full-time equivalent employees.

For more information on the department’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section of this report.

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

Raison d’être

The Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (the Office) was established to administer the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act), which came into force in April 2007. The Office is mandated to establish a safe, independent, and confidential process for public servants and members of the public to disclose potential wrongdoing in the federal public sector. The Office also helps to protect public servants who have filed disclosures or participated in related investigations from reprisal.

Mandate and role

The Office contributes to strengthening accountability and increases oversight of government operations by providing:

- public servants and members of the public with an independent and confidential process for receiving and investigating disclosures of wrongdoing in, or relating to, the federal public sector, and by reporting founded cases to Parliament and making recommendations to chief executives on corrective measures; and

- public servants and former public servants with a mechanism for handling complaints of reprisal for the purpose of coming to a resolution including referring cases to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal.

For more general information about the Office, see the “Supplementary information” section of this report.

Operating context and key risks

Operating context

The Office is an independent Agent of Parliament that receives disclosures of wrongdoing and complaints of reprisal from public servants working in federal organizations and Crown corporations, as well as members of the public. The Office is one element of a larger public sector integrity landscape that includes the Treasury Board Secretariat, which has overall responsibility for promoting ethical practices to public servants and disseminating knowledge about the Act. In turn, federal departments and agencies are responsible for administering these ethical practices and are accountable for establishing their own internal disclosure mechanisms in order to provide public servants with an alternative to disclosing wrongdoing to our Office. The Office has the exclusive jurisdiction, however, for responding to complaints of reprisal that result from protected disclosures.

The Office’s environment is a complex one that reflects its sensitive mandate. The work requires a high degree of care as each case we handle directly impacts the lives and reputations of individuals and organizations. Despite the existence of formal mechanisms to facilitate the disclosure of wrongdoing and to protect against and prevent reprisals, there still exists a culture of resistance to whistleblowing within the federal public sector due to various factors, including fear of reprisals. This plays a fundamental role in an individual’s decision to disclose wrongdoing. This informs outreach and engagement strategies to increase awareness of the whistleblowing regime, clarify the role of the Office and build trust in the Office.

Media and public interest have demonstrated the need and growing demand to respond to concerns about integrity in both the private and public sectors. Integrity regimes at provincial and municipal levels, as well as in other countries, vary in terms of legislation, mandate, powers, jurisdiction and organizational structures. They provide opportunities for benchmarking and sharing best practices and research.

As a micro-organization, there are challenges with regard to staff retention given limited internal growth opportunities. There are also challenges in sourcing, given that the labour market for key skilled positions, such as investigators, is very competitive.

New technologies are currently being assessed by the Office to improve management of its corporate knowledge and its administration, accessibility, case management and performance statistics.

In 2016-17, the Office launched a record number of investigations and at the same time participated in the legislative review of the Act. This had a direct impact on the timing of planned initiatives as resources were reassigned to address these changing priorities.

Key risks

Risks can arise from events that the Office cannot influence or by factors outside of its control, however, the Office must be able to monitor the risks and mitigate the impact in order to continue meeting its obligation of addressing disclosures of wrongdoing and complaints of reprisal in a timely manner. All of the organizational priorities contribute either directly or indirectly to mitigating the risk of increasing case volumes and/or complexity that may in turn impact the timeliness of completing case files.

The Audit and Evaluation Committee, composed of two members from outside the federal public service, serves as a strategic resource that provides objective advice and recommendations to the Commissioner regarding risk management, control and governance.

In 2016-17, the Office launch a record number of investigations which increase the risk of not achieving its service standards. The Office introduced and implemented a simplified review process and case management conferences. These new processes proved to be successful at effectively reducing response times and resulted in service standards being met.

Key risks

| Risks | Mitigating strategy and effectiveness | Link to the Office's Program | Link to Office priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

Increasing case volume The Office’s ability to respond in a timely manner can be affected by increases in case volume or complexity. This risk was identified in the 2016-17 report on plans and priorities. | Reporting on service standards ensured that management was informed and that actions were taken as appropriate. The Office implemented a simplified review process. This new process successfully reduced response times and enable the Office to meet its internal service standards. | Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program | Disclosure and reprisal management function that is timely, rigorous, independent and accessible |

Breaches of secure information This is critical for preserving confidentiality and maintaining trust in the Office. Sensitive or private information must be protected from potential loss or inappropriate access in order to avoid potential litigation, damaged reputation and further reluctance in coming forward. This risk was identified in the 2016-17 report on plans and priorities. | The Office has ongoing practices aimed at ensuring the security of information, which include security briefings and confidentiality agreements, random information security checks within premises, and controlled access for the storage of sensitive information. No security issues occurred in 2016-17 and work to mitigate this risk will continue in 2017-18. | Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program | Awareness and understanding of the whistleblowing regime |

Results: what we achieved

Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program

Description

The objective of the program is to address disclosures of wrongdoing and complaints of reprisal and contribute to increasing confidence in federal public institutions. It aims to provide advice to federal public sector employees and members of the public who are considering making a disclosure and to accept, investigate and report on disclosures of information concerning possible wrongdoing. Based on this activity, the Office will exercise exclusive jurisdiction over the review, conciliation and settlement of complaints of reprisal, including making applications to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal to determine if reprisals have taken place and to order appropriate remedial and disciplinary action.

Results

In 2016-17, the Office received a total of 81 disclosures of wrongdoing and 31 complaints of reprisal. We launched a record 36 investigations, doubling the number of investigations compared to the year before, while meeting our targets for all our service standards. We tabled 2 case reports in Parliament that dealt with serious matters of wrongdoing, both regarding harassment within the public service. In addition we successfully conciliated 2 reprisal cases that were under active investigation.

To ensure a disclosure and reprisal management function that is timely, rigorous, independent and accessible, the Office launched a LEAN project, in 2015-16, to review the workflow of case analysis and investigations. The project continued forward in 2016-17 with the implementation of a simplified process for low complexity files and regular case management conferences for reprisal complaints. The LEAN initiative will continue in 2017-18 with a focus on investigation processes.

The Office met on a regular basis with its cross functional working group to continue work on identified priorities, update its list of issues, and work on a number of new policy instruments including a process map for conciliation and a standard operating procedure for reconsideration requests.

The Office continued to review and assess its operational manual. This is an evergreen document which identifies the links between legal principals, policy instruments and operational processes and reflects the evolution of the Office.

In 2016-17, the Office updated its international engagement strategy to create awareness and understanding of the whistleblowing regime. The Office also completed the evaluation of the outreach program on March 31, 2017. Based on the evaluation, the outreach strategy will be updated in 2017-18.

The Office commissioned and published a research paper entitled: “The Sound of Silence: Whistleblowing and the Fear of Reprisal” which is available in both official languages on the Office’s Web siteFootnote 1. The paper is divided into three sections. The first examines the psychology of whistleblowing, including fear of reprisal. The second section highlights the factors that influence our decisions about whether to speak up. The paper concludes with a series of evidence-based recommendations and strategies, which may be implemented to foster a safer environment where people feel more comfortable sharing their concerns.

In 2016-17, the Office continued to engage with public servants by attending 18 outreach events reaching approximately 8,400 public servants and distributing over 8,500 informational materials. We hosted an annual meeting with our federal, provincial and territorial counterparts to discuss achievements, challenges and best practices. In addition, we held three Advisory Committee meetings and attended monthly Internal Disclosure Working Group meetings, an inter-departmental working group primarily comprised of Senior Officers for Internal Disclosure who share best practices and lessons learned with regard to the management of the internal disclosure process.

Perhaps the most important development to report on this year was the launch of the highly-anticipated review of the Act, the legislation that created our Office and the federal public sector whistleblowing regime. The Office actively participated in this legislative review of the Act and published 16 recommendations to strengthen and improve effectiveness of the disclosure regime. The 16 proposals are on the Office’s websiteFootnote 2.

Results achieved

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2016–17 Actual results | 2015–16 Actual results | 2014–15 Actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The disclosure and reprisal management function is efficient | Decision whether to investigate a complaint of reprisal is made within 15 days | 100% | March 2017 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| General inquiries are responded to within one working day | 80% | March 2017 | 99% | 90% | 99% | |

| Decision whether to investigate a disclosure of wrongdoing is made within 90 days | 80% | March 2017 | 88% | 33% | 84% | |

| Investigations are completed within 1 year | 80% | March 2017 | 82% | 50% | 86% | |

| The disclosure and reprisal cases are addressed with decisions that are clear and complete. | Successful applications for judicial review in comparison to the total number of cases received over three years | No more than 2% | March 2017 | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2016–17 Main Estimates | 2016–17 Planned Spending | 2016–17 Total Authorities Available for Use | 2016–17 Actua Spending (authorities used) | 2016–17 Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,564,227 | 3,564,227 | 3,746,113 | 2,779,946 | (784,281) |

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2016–17 Planned | 2016–17 Actual | 2016–17 Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|

| 23 | 20 | (3) |

Further information on the Office’s program is available on its websiteFootnote 3 and in the TBS InfoBaseFootnote 4

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are: Management and Oversight Services; Communications Services; Legal Services; Human Resources Management Services; Financial Management Services; Information Management Services; Information Technology Services; Real Property Services; Materiel Services; and Acquisition Services.

Results

The Office is operating with a small Internal Services team. To successfully deliver services to the program it relies on several shared-services agreement. In 2016-17, the Office approved and continued its major agreement with the Canadian Human Rights Commission of Canada to receive services in financial management, information management, information technology, human resources management and other administrative services.

The success of a micro organization is also dependent on hiring, retaining and engaging employees with the knowledge, skills, and experience who work as a team and independently.

In 2016-17, the Office implemented the revised Public Service Commission Appointment framework to meet the staffing needs of the Office. In particular, it revised its internal policies and guidelines on selection and appointment processes.

Efforts were made in 2016-17 to start creating pools of qualified case analysts and investigators. However, because of increase in investigations and the launch of the legislative review, this planned initiative was completed in early 2017-18.

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2016–17 Main Estimates | 2016–17 Planned Spending | 2016–17 Total Authorities Available for Use | 2016–17 Actual Spending (authorities used) | 2016–17 Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,898,247 | 1,898,247 | 1,851,445 | 1,543,753 | (354,494) |

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2016–17 Planned | 2016–17 Actual | 2016–17 Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 6 | (1) |

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

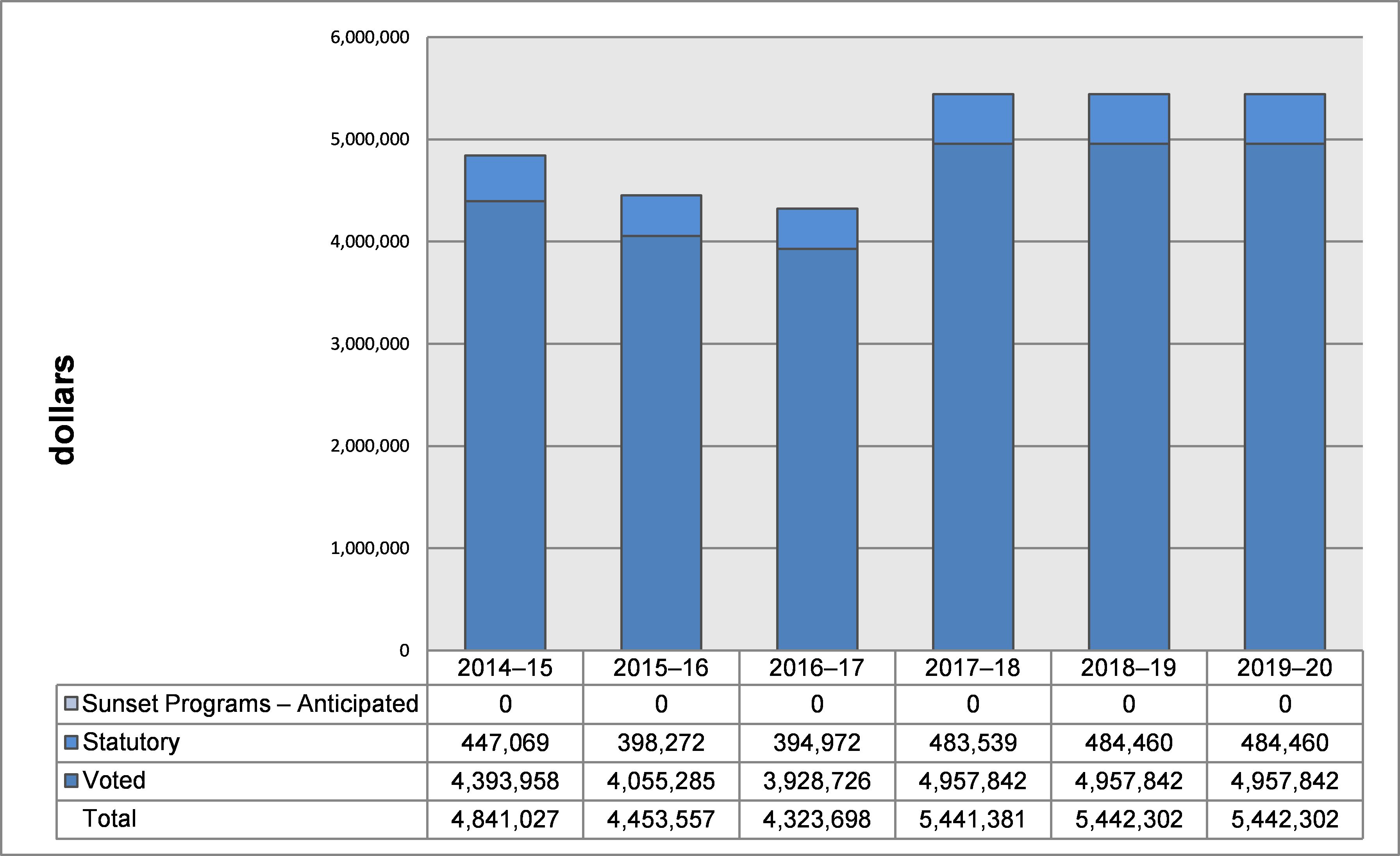

The trends in spending and human resources are summarized in the following graph and tables. They show the variation in the Office's used and planned resources over a six-year period, which results from activities carried out by the Office’s Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program and its Internal Services.

Actual expenditures

Departmental spending trend graph

Text Version

This bar graph illustrates the spending trend for the Office’s program expenditures related to actual spending for fiscal years 2014–15, 2015-16 and 2016–17, and planned spending for fiscal years 2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20. Financial figures are presented in dollars along the y axis, increasing by $1 million increments to $6 million. These are graphed against fiscal years 2014–15 to 2019–20 on the x axis.

There are three items identified for each fiscal year, the first one being sun-setting programs, the second relates to statutory items, comprised of contributions to employee benefit plans (EBP), and the third, the Office's program expenditures (Voted).

The Office has only one program, hence no sunset program was recorded or is anticipated.

In 2014–15, actual spending was $445,069 for statutory items and $4,393,958 for program expenditures.

In 2015–16, actual spending was $398,272 for statutory items and $4,453,557 for program expenditures.

In 2016–17, actual spending was $394,972 for statutory items and $3,928,726 for program expenditures.

Planned spending for statutory items is expected to increase to $483,539 in 2017-18 and to $484,460 in 2018-19 and 2019-20. However, this will depend on the Treasury Board EBP rate.

Planned spending for program expenditures will remain the same for fiscal years 2017–18 to 2019–20 in the amount of $4,957, 842. This estimated amount includes new project spending in information technology infrastructures and office accommodation.

This bar graph illustrates the spending trend for the Office’s program expenditures related to actual spending for fiscal years 2014–15, 2015-16 and 2016–17, and planned spending for fiscal years 2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20. Financial figures are presented in dollars along the y axis, increasing by $1 million increments to $6 million. These are graphed against fiscal years 2014–15 to 2019–20 on the x axis.

There are three items identified for each fiscal year, the first one being sun-setting programs, the second relates to statutory items, comprised of contributions to employee benefit plans (EBP), and the third, the Office's program expenditures (Voted).

The Office has only one program, hence no sunset program was recorded or is anticipated.

In 2014–15, actual spending was $445,069 for statutory items and $4,393,958 for program expenditures.

In 2015–16, actual spending was $398,272 for statutory items and $4,453,557 for program expenditures.

In 2016–17, actual spending was $394,972 for statutory items and $3,928,726 for program expenditures.

Planned spending for statutory items is expected to increase to $483,539 in 2017-18 and to $484,460 in 2018-19 and 2019-20. However, this will depend on the Treasury Board EBP rate.

Planned spending for program expenditures will remain the same for fiscal years 2017–18 to 2019–20 in the amount of $4,957, 842. This estimated amount includes new project spending in information technology infrastructures and office accommodation.

The decrease in total spending in the last three years reflects lower operating project spending as well as periods of vacancies and time it takes to staff new positions.

The Office is planning to gradually spend the total authorities available for use starting in 2017-18, as vacant positions continues to be staffed, operational projects are completed and new projects for information technology and office accommodation are implemented to continue working efficiently towards our priorities.

As of March 31, 2017, the Office had 26 employees. The variance of 4 full-time equivalents is attributed to normal turnover in personnel. The future level of human resources may be affected by the results of the legislative review of the Public Servant Disclosure Protection Act.

It is also noted that there is a shift, from 2014-15 to 2016-17, between Internal Services and the Office’s program, in both actual spending and full-time equivalents. This can be explained by a shift in the alignment of activities and the application of the 2016 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Guide on Recording and Reporting of Internal Services Expenditures. This guide clarifies what constitutes Internal Services expenditures versus program expenditures.

Budgetary performance summary for Programs and Internal Services (dollars)

| Programs and Internal Services | 2016–17 Main Estimates | 2016–17 Planned Spending | 2017–18 Planned Spending | 2018–19 Planned Spending | 2016–17 Total Authorities Available for Use | 2016–17 Actual Spending (authorities used) | 2015–16 Actual Spending (authorities used) | 2014–15 Actual Spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program | 3,564,227 | 3,564,227 | 3,550,898 | 3,553,133 | 3,746,113 | 2,779,946 | 2,644,497 | 2,692,847 |

| Internal Services | 1,898,247 | 1,898,247 | 1,890,483 | 1,889,169 | 1,851,445 | 1,543,753 | 1,809,060 | 2,148,180 |

| Total | 5,462,474 | 5,462,474 | 5,441,381 | 5,442,302 | 5,597,558 | 4,323,699 | 4,453,557 | 4,841,027 |

Actual human resources

Human resources summary for Programs and Internal Services (full-time equivalents)

| Programs and Internal Services | 2014–15 Actual | 2015–16 Actual | 2016–17 Planned | 2016–17 Actual | 2017–18 Planned | 2018–19 Planned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program | 18 | 19 | 23 | 20 | 23 | 23 |

| Internal Services | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 26 | 26 | 30 | 26 | 30 | 30 |

Expenditures by vote

For information on the Office’s organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2017Footnote 5.

Alignment of spending with the whole-of-government framework

Alignment of 2016–17 actual spending with the whole-of-government frameworkFootnote 6 (dollars)

| Program | Spending Area | Government of Canada activity | 2016–17 Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program | Government Affairs | A transparent, accountable and responsive government | 2,779,946 |

Total spending by spending area (dollars)

| Spending Area | Total Planned Spending | Total Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Affairs | 0 | 0 |

| Social Affairs | 0 | 0 |

| International Affairs | 0 | 0 |

| Government Affairs | 3,564,227 | 2,779,946 |

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The Office’s financial statements [unaudited] for the year ended March 31, 2017, are available on its websiteFootnote 7.

Financial statements highlights

The financial highlights presented below are drawn from the Office’s financial statements which are prepared on an accrual accounting basis while the planned and actual spending amounts presented elsewhere in this report are prepared on an expenditure basis. As such, amounts differ.

Condensed Statement of Operations (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2017 (dollars)

| Financial Information | 2016–17 Planned Results | 2016–17 Actual | 2015–16 Actual | Difference (2016–17 actual minus 2016–17 planned) | Difference (2016–17 actual minus 2015–16 actual) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 6,236,239 | 4,923,067 | 5,098,876 | (1,313,172) | (175,809) |

| Total revenues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | 6,236,239 | 4,923,067 | 5,098,876 | (1,313,172) | (175,809) |

Condensed Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) as at March 31, 2017 (dollars)

| Financial Information | 2016–17 | 2015–16 | Difference (2016–17 minus 2015–16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 849,583 | 828,904 | 20,679 |

| Total net financial assets | 522,640 | 494,430 | 28,210 |

| Departmental net debt | 326,943 | 334,474 | (7,531) |

| Total non-financial assets | 177,188 | 149,958 | 27,230 |

| Departmental net financial position | (149,755) | (184,516) | 34,761 |

The 2016-17 actual total expenses of $4.9 million reflect a decrease of $0.175 million as compared with 2015-16 and, is primarily due to lower operating project spending as well as periods of vacancies and time required to staff new positions.

The total liabilities, as at the end of the year, were $0.8 million, composed of accounts payable, accrued salaries, employee future severance benefits and vacation pay liabilities. The total financial assets as at the end of the year were $0.5 million and reflect amounts due from the Consolidated Revenue Fund and amounts in accounts receivable (primarily from other government departments). Departmental net debt of $0.3 million, calculated as the difference between total net liabilities less net financial assets, has decreased slightly compared to the previous year. The net debt indicator represents future funding requirements to pay for past transactions and events, and is one indicator of a department's financial position. The total non-financial assets reflect the net book value of capital assets as at March 31 and have increased as new investments in capital were made in 2016-17.

Supplementary information

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Minister: The Honourable Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board

Institutional head: Joe Friday, Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

Ministerial portfolio: Treasury Board Secretariat

Enabling instruments: Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act, S.C. 2005, c. 46

Year of incorporation: 2007

Other: The Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada supports the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, who is an independent Agent of Parliament.

Reporting framework

The Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner’s Strategic Outcome and Program Alignment Architecture of record for 2016–17 are shown below.

- Strategic Outcome: Wrongdoing in the federal public sector is addressed and public servants are protected in cases of reprisal

1.1 Program: Disclosure and Reprisal Management Program

Internal Services

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the Office’s websiteFootnote 8:

- Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy

- Internal audits and evaluations

- Response to parliamentary committees and external audits

- User fees, regulatory charges and external fees

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax ExpendituresFootnote 9. This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs. The tax measures presented in this report are the responsibility of the Minister of Finance.

Organizational contact information

60 Queen Street, 7th Floor

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5Y7

Canada

Telephone: 613-941-6400

Toll Free: 1-866-941-6400

Facsimile: 613-941-6535 (general inquiries)

http://www.psic-ispc.gc.ca

Appendix: Definitions

Appropriation (crédit)

Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

Budgetary Expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

Core Responsibility (responsabilité essentielle)

An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a Core Responsibility are reflected in one or more related Departmental Results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

Departmental Plan (Plan ministériel)

Provides information on the plans and expected performance of appropriated departments over a three‑year period. Departmental Plans are tabled in Parliament each spring.

Departmental Result (résultat ministériel)

A Departmental Result represents the change or changes that the department seeks to influence. A Departmental Result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

Departmental Result Indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

A factor or variable that provides a valid and reliable means to measure or describe progress on a Departmental Result.

Departmental Results Framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

Consists of the department’s Core Responsibilities, Departmental Results and Departmental Result Indicators.

Departmental Results Report (Rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

Provides information on the actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

Evaluation (évaluation)

In the Government of Canada, the systematic and neutral collection and analysis of evidence to judge merit, worth or value. Evaluation informs decision making, improvements, innovation and accountability. Evaluations typically focus on programs, policies and priorities and examine questions related to relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. Depending on user needs, however, evaluations can also examine other units, themes and issues, including alternatives to existing interventions. Evaluations generally employ social science research methods.

Full-time Equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person‑year charge against a departmental budget. Full‑time equivalents are calculated as a ratio of assigned hours of work to scheduled hours of work. Scheduled hours of work are set out in collective agreements.

Government-wide Priorities (priorités pangouvernementales)

For the purpose of the 2016–17 Departmental Results Report, government-wide priorities refers to those high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the 2015 Speech from the Throne, namely: Growth for the Middle Class; Open and Transparent Government; A Clean Environment and a Strong Economy; Diversity is Canada's Strength; and Security and Opportunity.

Horizontal Initiatives (initiative horizontale)

An initiative where two or more federal organizations, through an approved funding agreement, work toward achieving clearly defined shared outcomes, and which has been designated (for example, by Cabinet or a central agency) as a horizontal initiative for managing and reporting purposes.

Management, Resources and Results Structure (Structure de la gestion, des ressources et des résultats)

A comprehensive framework that consists of an organization’s inventory of programs, resources, results, performance indicators and governance information. Programs and results are depicted in their hierarchical relationship to each other and to the Strategic Outcome(s) to which they contribute. The Management, Resources and Results Structure is developed from the Program Alignment Architecture.

Non-budgetary Expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

Performance (rendement)

What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

Performance Indicator (indicateur de rendement)

A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

Performance Reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement)

The process of communicating evidence‑based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

Planned Spending (dépenses prévues)

For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts that receive Treasury Board approval by February 1. Therefore, planned spending may include amounts incremental to planned expenditures presented in the Main Estimates.A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports.

Plans (plans)

The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead up to the expected result.

Priorities (priorité)

Plans or projects that an organization has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired Strategic Outcome(s).

Program (programme)

A group of related resource inputs and activities that are managed to meet specific needs and to achieve intended results and that are treated as a budgetary unit.

Program Alignment Architecture (architecture d’alignement des programmes)

A structured inventory of an organization’s programs depicting the hierarchical relationship between programs and the Strategic Outcome(s) to which they contribute.

Results (résultat)

An external consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

Statutory Expenditures (dépenses législatives)

Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

Strategic Outcome (résultat stratégique)

A long-term and enduring benefit to Canadians that is linked to the organization’s mandate, vision and core functions.

Sunset Program (programme temporisé)

A time-limited program that does not have an ongoing funding and policy authority. When the program is set to expire, a decision must be made whether to continue the program. In the case of a renewal, the decision specifies the scope, funding level and duration.

Target (cible)

A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

Voted Expenditures (dépenses votées)

Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an Appropriation Act. The Vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.